|

|

|

|||||

|

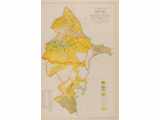

This note has to do with Kuba, certain of its weaving villages, and one of its ethnic groups. Kuba khanate was small and in history (from its beginning in the 15/16th c.) for the most part unimportant. On the coastal trade route north, it was agricultural and relatively prosperous. The ruling family usually managed to keep its distance from Iranian rule, and moved from its citadel to live in Kuba town in 1735. [1] Kuba was a weaving powerhouse. This role has been out in the open for some time; [2] the following paragraphs go into greater detail concerning an Iranian language group termed Tats by Turks.

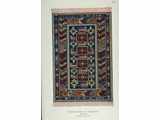

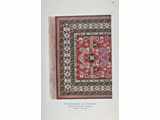

By the turn of the 20th century the government’s kustar’ support program had reacted to widespread design deterioration and had completed an oblast’-wide (Caucasia) survey in an effort to establish authentic motifs and patterns. An active support program was underway – yarns, dyes, equipment (Kuba loom, below), marketing assistance – this last extending to international expositions (Paris, 1900, Caucasus section entrance, below). Some villages perhaps did own the copyright, so to speak, for a particular pattern; however, since other locales copied, a good view would be to consider that place and pattern nomenclature c. 1900 are as accurate as they can be but that production sites vary, as, for example, the “Shirvan-Chichi” type. The Western travel literature makes it clear that weaving in Kuba district was a traditional activity and that in part was always in commerce. In brief: the Spaniard Gamba (1813) mentioned what appears to be pile weaving in Dividge, the excellent rugs of Kuba town, and the villagers of Ziakour [sic] who “excel” in the making of rugs; Halen (1820) identified carpets as the principal element of economic activity in Tchiakour [sic] with a product which was “superior” in coloration and patterns; Zubov (1820’s) recalled that the Viceroy of Caucasia had copies of Gobelein tapestries made in Kuba; Klaproth (1827) noted the exchange of rugs by Kuba town with upland villages for local products; and, the craft exposition in Tiflis of 1889 included a Konakend sumac dated 1802. [3] The Rugs A hard and fast rule can’t be laid down as to Kuba structure because of the likelihood of exceptions but a somewhat depressed warp can be taken as a marker. Such was the opinion of the late Najiba Abdullaeva and she knew her stuff. There is a detailed written description of the Kuba weaving technique which can be read to substantiate this view, but words are ineffable in this context and no conclusion is possible. [4] End finishes could be either braided warps or a short flatwoven strip, color irrelevant. A 1901 interview-based review of the principal weaving villages recited the problems typical for the period: poor prices and weaver wages, incursion of synthetic dyes, some increep of cotton warps. The most notable finding, however, was that vegetable dyes were still dominant, still the case in 1912 per another kustar’ program source. [5] Also of central interest, pile rugs were not of consequence until well into the 19th century. The survey of these 27 villages identified some start times as: 50 years previously – 2 villages (including Chi-Chi); 30 years – 2; 20-25 yrs. – 5 (including Zeikur, Imam-Kuli-Kend); and 10 yrs. -- 7. Prior to this the flatwoven technique prevailed --- kilims, sumacs, and bags. [6] The focus of the survey was economic, how to better the income of the weavers. By the mid-19th c., a generation after the Russian conquest, the needs of villagers for cash had increased as items previously not in good supply – kerosene, sugar, salt, and the like – had become virtual necessities. Carpet-making shifted from meeting home household needs plus casual local commerce to a market-oriented economic enterprise – described at some length in the schoolmasters’1888 survey [7] -- with thousands of weavers, many of whom needed to purchase wool; in some situations it was necessary to hire additional help. In 1901 certain villages were in the grip of a decline (poor prices, poor workmanship); others were on the upswing. The atmosphere at the time was revival and expansion of production; one element of this was the “taking of them [designs] from Persian rugs.” [8] The evident response to a growing market plus a prior history of predominantly flatwoven items indeed suggests that Persian patterns were a new development. Cartoons of authentic designs were distributed in 1905/06 and some subsequently showed up in the Kuba section of the 1912 all-Russian craft exposition. [9] In a report covering the year1909 the Caucasus Kustar’ Committee calculated that 50% of Kuba district cash income came from rug sales. [10] The Tats A case can be made that Tat products represent the gold standard of Kuba rugs. The time of this group’s entry into eastern Caucasia is obscure, be they descendants of Sassanid Iranians or later arrivals. Tat speakers could be Muslim (the overwhelming majority and largely Shiite), Christian, or Jewish. A 19th c. monograph giving the background of the Tats, with concentration on the so-called mountain Jews, furnishes considerable information concerning Tat history, and cites a mid-century study which characterizes Tats as “commoner Persians” and “awkward, hick persons”. [11] Some of the current discourse about them asserts they are direct descendants of Sassanian Iranians who had “migrated back” to coastal Azerbaijan. [12] Arrival some time between the 9th and 12th centuries is the view of one thoughtful student. [13] Assimilation into Azeri culture has been going on for a long time and continues. The life style has always been sedentary. Population counts of the group have diminished considerably over time. Of note is their Kuba presence as well as that on the Apsheron peninsula (in buff), per the map above. [14] The 1897 census gave the population of Kuba district as Tat, 46,430 (24%); Azeris, 70,150 (38%). [15] Ethnographic work in the 1950’s identified Tat village locations as: in Kizin area, 27; in Siazan, 4; in Divichi, 16; in Konakend, 18; and, in Kuba town and vicinity, 15. [16] Mid-20th c. population numbers are perhaps a little squishy, in the range of 20—30 thousand. THE 1924 MOSCOW EHIBIT A review of the 1924 carpet exhibition held in the ethnographic section of the Russian Museum contains a strong tilt toward Tats: designation of the principal Caucasia weaving centers as Karabakh (Azerbaijanis) and Kuba (Tats). The author makes an interesting observation concerning color “…exclusively in Tat rugs it is almost never [that] a red coloration (in the aggregate of its hue) can be seen as dominant.” [17] This characteristic could possibly reflect an esthetic preference since madder was still relatively abundant, left over from its commercial boom in the mid-19th c. THE 1926 KUBA EXHIBIT Zakgostorg held a 2-day exhibition of 200 rugs in Kuba town in March, 1926. Old rugs were for the most part barred; there were 10 prize winners. Perebedil got three; one was for an ‘old’ pattern “to this day popular in cheap market-place rugs”. An Imam-Kuli-Kend piece with the date 1926 (below, paired with a Zakgostorg lithograph) was “nearly the most archaic.” Imam-Kuli-Kend beginning in 1912, together with Kuba town, became a center for patterns, yarns, dyestuffs, and training, as well as marketing assistance aimed at avoiding exploitation of weavers. [18] Rugs illustrated below are for patterns of Tat villages and are from plates in Isaev[19] which are reproductions of Zakostorg lithographs (1928) of items available for export via orders placed in its Leipzig office. In descending left/right order they are: Perebedil’, burma pattern, and Perebedil’, Herat pattern; Zeiva, zeiva pattern, and Chi-chi, - khrda pattern; Konakend, namazlik, and Konaked, khanchesa pattern. . [1] Istoria

Azerbaidzhana, Vol I, pp. 340—341, p. 365.

[2]See Caucasian

Carpets and Covers, Wright, Richard E. and Wertime, John

T., 1995, p. 62 ff.

[3]Erroneously

called pile in Caucasian Carpets and Covers.

[4]Kara-Murza,

I. M., Kustarnaya promyshlennosti’ na Kavkaze, vypusk’ 1,

kovrovyi promycel’ v Kubinskom’ uezde, 1902.

[5]Second

All-Russian Empire Kustar’ Exhibition, 1913.

[6] Kara-Murza, op.

cit., p. 29.

[7] Pyshenko,

Vladimir, Kuba uezd, promyslovyya zanyatia v nekotoryk nascellenykh

punktakh Zakavkaz’ya, in Sbornik materialov dlya

opisanya i mestnostei i plemen Kavkaza, Vol. XI, 1891, pp.

151—154.

[8] Kara

Murza, op. cit., p. 29.

[9] Zummer,

V. M., Sovremennye kubinskie kovry, izvestiya o-va obskedovaniyai

izucheniya Azerbaidzhana, No. 3, 1926, pp. 185—193.

[10] S’yzd’ dyatelei

po kustarnoi promyshlennosti 1910 goda, p.2,

[11] Miller,

Vsev., Materialy dlya izucheniya Ebreisko-Tatskago yazyka, Imperial

Academy of Science, 1892; Recherches sur les dialects

Persans, Casan, 1851, p.69.

[12]Mamedov,

Aliaga, Aspects of the Contempary Ethnic Situation in Azerbaijan, “The

Tats”, The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire, www.eki.ee/books/redbook/tats.shtml.

[13] Frye,

R. N., “Historical Evidence of the Movement of People in

Iran”, The Muslim East: Studies in Honor of Julius Germanus, 1974,

pp. 221-223; See also Donald L. Stilo, “The Tati Language

Group in the Sociolinguistic Context of NW Iran and Transcaucasia”, Iranian

Studies.

[14] Zapiski

Kavkazskago otdela…, Etnograficheskkye karty’, Supplement

Vol. 18, 1896.

[15] Pervaya

vceobsh perepic’ naceleniya Rossiiskoi Imperii, Bakinskaya

gubernia, Vol. 61, 1897.

[16] Grunberg,

A. L., Yazyk Severoazerbaidzhanskikh Tatov, 1963.

[17] Miller,

A., Kovrovye izdeliya vostoka, 1924, p.5, p.9, p. 14,

p. 22.

[18] Zummer, op.

cit., p. 190.

[19] Isaev,

M. D., Kovrovoe proizvodstvo Zakavkaz’ya, 1932.

Copyright � Richard E. Wright, All Rights Reserved |