Support for peasant home craft industry began as a charitable activity in European Russia but before long became a government program and stayed that way, both Czarist and Bolshevik. A full organizational apparatus was slow in coming to Caucasia (c. 1900) although ad hoc efforts were underway earlier. One was a large carpet exhibition in Tiflis, [now Tblisi, Georgia] the capital of Caucasia, a special administrative region linked directly to the Czar via a Viceroy. The exhibit’s records list exhibitors by district and carpet type, and identify prize winners. Names are not of interest and will be omitted here; what was woven, where, is important. The weavers, however, are known although at that time material would have been submitted in the husband’s name.

A 1968 academic journal article describes the affair in great detail.1 How to interpret the text is somewhat difficult. Poorly written, it points out the obvious and is very repetitive. The text is in Azeri. Any contemporary report about the exhibit would have been in Russian; the frequently appearing term Azerbaijan would not have been present. Confusingly, some the report sounds as though it could have been written at the time of the show. But it was not; the text could, however, convey the substance of thoughts expressed in 1889 and perhaps include some of that language. The article’s footnotes certainly create the possibility 2 but it is only a possibility. There is quite a bit of wool-gathering about designs, much of it outdated and not of interest. The material cries out to be abridged. But, it would not be good to do so; some details of interest might get excluded. Place and object names appear as spelled in the text and will be used in this translation. Indeed, the Azeri spelling may be a bit more authentic than the Russian. The exhibit gives a good picture of the weaving culture at the threshold of the export boom. The considerable variation in object type and their widespread geographic distribution (many place names the rug world has never heard of) constitute an interesting snapshot in time. The article’s judgment that the exhibit was a good beginning for support of weaving is valid whether originating prospectively in 1890 or retrospectively in 1968. And, a number of particulars are revealing. The preponderance of flatwoven articles over pile is perhaps the most significant. There are, as well, multiple small details: the Shia names among the exhibitors, the existence of a collection in a local kustar’museum, the emerging presence of a government home craft support apparatus (typically the local school master), the surprisingly early corruption of design in Shusha 3 and so forth and so on. Here is the text: “One of these exhibits which was organized in the second half of the 19th century was ‘Caucasian Agricultural and Industrial Objects’ in Tiflis in 1889. The basic goal of the exhibit was to learn about the situation of agriculture and industry in the Caucasus and to develop them in the future. In order to display local industrial products manufactured in the Caucasus at the exhibit representatives went to the most remote areas of the country and explained the objectives and duties of the exhibit to the population of the Caucasus. Participants at the exhibit could only be inhabitants of the Caucasus and Transcausus areas. “Artists and weavers and carpetmakers from the various guberniya [provinces] took part in the exhibit. The displaying of goods produced by artists living in Muslim territories was preferred at the exhibit. “Raw materials characteristic of districts of Azerbaijan and which played a basic role in the life and economy of the inhabitants, plants used in dying yarns for carpets, and carpet products were also shown. “Since the development of local industry was at a low level and the more active participation of craftsmen at future exhibits was desired it was necessary to stimulate local artists. The Minister of State Land set aside money for the purchase of work by craftsmen in its crafts section and awarded money, medals and certificates with the goal of gaining the interest of local craftsmen. “Despite the many displays in the craft department of the exhibit, few of these works were submitted by the craftsmen themselves. The great majority was collected administratively. The objects gathered administratively were collected from various places in the Caucasus, including the guberniyas of Baku and Elizavetpol (Ganja) and the Zagatala region of Azerbaijan. “The carpet department at the exhibit was especially distinguished. The carpets and carpet products assembled here were hung from all the walls and even the ceilings of the section. At first glance the craft section looked like a tent assembled from carpets. Among the products gathered here the carpets, palas, kilims, sumakhs, jejims, vernis, chuvals, mafresh, horse chuls [covers] and others were distinguished by their art and variety. “Muslim women who had come from Shusha district, because of an order given to the local committee, demonstrated the carpet weaving process before the eyes of the spectators at a carpet weaving workshop which had been organized at the exhibit. “Many carpets and carpet products were brought from various districts of Azerbaijan -- Baku, Guba, Javad, Shamakhy, Lankaran, Ganja, Gazakh, Shusha, Jabrayl, Goychay, Shaki and Zagatala. [Exhibitor names have been omitted from this translation. Everyone is an oghlu. In the translation’s listing of items, those between semicolons separated by commas indicate different exhibitors.] “A list is given below of the carpet and carpet products displayed from locations in Zagatala. “From Suvagil – jejim, woolen stockings, broadcloth (mahud); Zagam – chuval, three woolen stockings, wool yarn; Taly – woolen stockings, gyzy, woolen stockings; Chary – saddle bags; Govakhkel – saddle bags and chuval ; Gakh – two chuvals, saddle bags, jejim; Padar – jejim, shawl in white and black colors; wool felt; saddle bags, four silk jejims. “From Elizabethpol district – five carpets. “Carpet and carpet products exhibited from towns in the Jebrayl district: Gojaly – two mefresh; Gochamadli – verni and two mefresh; Seyidahmadli – two mefresh, two chuval; Hajyly – some rugs, a palaz, zili, and horse chulu; Dashkasan – palas, jejim; Babaly – palaz; Shykhly – palaz, small carpet (khalcha), palaz, horse chulu; Dordchinar - palas, verni, and jejims; Mehrali – zili, zili, zili and palaz; horse chulu and some carpets (khalcha); Yaglovend – horse chulu and jejims, zili; Garadagly – verni, verni; Aghaly – zili; Behmenli – verni, verni; Kovshutlu – palaz; Garakhanbeyli – some carpet (khalcha); Marazaly – carpet and horse chulu; Merdinli – carpet; Abdulrehmanbeyli – horse chulu, saddlebags and salt pouch; Aybatanly – saddle bags; Gerakhly – jejim. “Carpet and carpet products from towns in Shusha district: “Veysalli – a national carpet; Tugh – palaz; Gajar – chuval; Khalfaradinli – jejim woven in half silk. “Now the composition of some of the carpet and carpet products displayed in the 1889 exhibit will be explained.

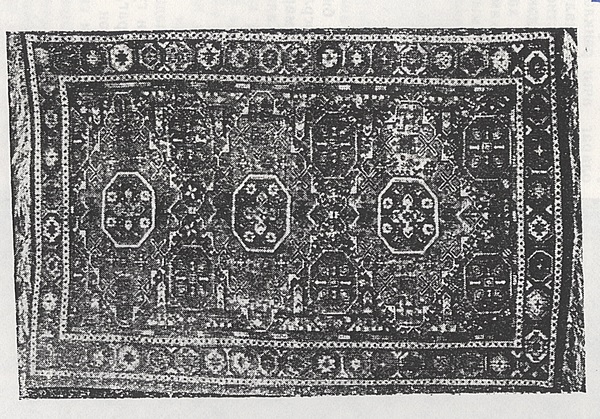

“The carpet in [this] illustration was woven in 1802 and is called a “Gonakend” carpet. At first glance the gols (the three central areas surrounded by octagonal borders) attract attention (gol normally means lake or body of water surrounded by land). These gols consist of three large gols arranged in sequence along the central axis of a carpet which is vertical in direction in its space composition. An eight-cornered medallion is located in the central part of each gol so that it stands prominent in the interior illustration. [The illustration in the report is labeled “Gonakend”, a Kuba village, literally “talking town”. Calling this textile a carpet is a bit startling since its pattern is standard for sumaks. The exhibition organizers and the author of the 1968 article certainly knew that carpet means pile. The exhibit either uncovered something of interest, or there was an illustration mix-up (which seems unlikely), or sloppy use of the term kalcha. The date if read correctly is well before the large export market and possibly -- quite a stretch -- could be a pile archetype of the latter day sumak.] “At both ends of the large gols in this space – on the right and on the left – eight-cornered medallions and the large gols an element shaped like a partial inscription is given. These medallions are found in old “sumakhs”, in carpets (kalcha) of old Guba compostion. Between the eight-cornered medallions and the large gols an element shaped like a partial inscription is given. One also finds this in old Guba carpets. Perhaps this is reminiscent of the partial inscription form. As for the space in the carpet which remained empty, filling elements are located in it. “On the right and left side of the last gol is the hijra (Islamic year) date showing the year in which the carpet was woven (1217/1802). [To repeat: The naming of this textile raises eyebrows. The author either is wrong or the item is quite interesting. Due diligence would indicate favoring the sloppy language explanation.] “At this point we have to say that we come across gol carpets among Baku, Absheron, Shirvan, Gazak and Garabagh types of carpets. But the gols in the Gonakend carpets are distinguished from the gols in these carpets through their form, esthetic beauty and refinement. These gols recall somewhat the gols in “Sumakhkhalcha”(“Sumakh carpet”) products of Azerbaijan’s Gusar area. We have to say that with regard to composition there is a similarity between the carpets of Gonakend and those of Derbend. Coming to the outer margin of the carpet we have to say that the interior area of the carpet is surrounded by a margin called “gol” inside of which is a depiction of an animal on every side; as for the margin area, it is surrounded by an inner border on every side. “Coming to the color characteristics one can say that Gonagkend carpets are rendered with a deep blue background in most cases. As for of the carpet’s margins, it [sic] is woven with open colors in distinction to its interior area. In addition to this, various colors are also used in the carpet. The date on the rug also proves that the basic raw material dye of the rug yarns was attained from natural colors taken from the plant kingdom. “Along with all this, there are also a number of flaws in the carpet. [Unspecified.] “The “Gonakend” carpet displayed at the exhibit, a product of the 18th century, is one of the art works which illuminate the art of the Azerbaijan carpet. “The most interesting of the carpets woven in the 18-19th century is the Talysh rug with the “Buta” (bud, as in rose bud) composition.

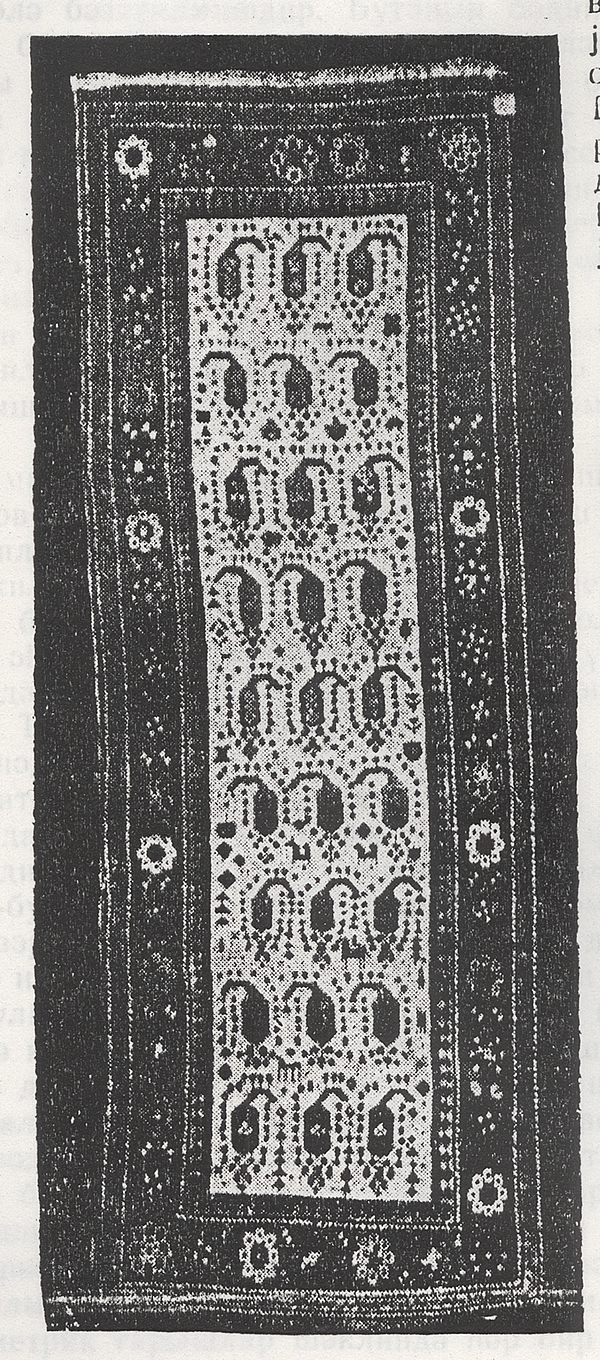

“The composition of the interior area of this carpet consists of a series of buds which are organized in rows. These buds are organized in both horizontal and vertical rows. Despite the fact that the bud elements rendered in the interior area are woven in the same structure, the rows of buds differ from one another. While the view of the buds that is given to the right in the first row, it is directed to the left in the second row. Thus, the composition’s placement is correctly located trough the sequential rows of buds. “The bud element, which occasionally conveys a religious content, bears various names in various places according to convention; i. e. flower (gul), almond (badam), peacock (tovuz kushu), etc. We come across this ornamentation in fragments from Kasmir, in rugs produced in Iran, in engravings, buildings, or ceramic products, on wood and copper, in jewelry and carvings. But the bud which is considered to be the richest element in the ornamental art of Azerbaijan is a symbol of the shape of a flame. “The beauty of the bud rendered in the Talysh carpet lies in the fact that this bud differs with respect to its special form and beauty from the buds rendered in carpets produced in Baku, Shirvan, Javad, Shusha, Jabrayl and other districts which are known in Azerbijan carpet science. The basic aspect which interests us in this carpet is the fact that a new, complexly formed bud element hitherto unknown to science is successfully used in its composition. The areas above every bud in the carpet have been adorned with various ornamentations. One of the aspects which increase the esthetic beauty of the bud is that it is surrounded by ornaments. The carpet maker, by rendering the bud within the ornamentation, has made them resemble the sparks emanating from a flame. One of the factors supporting this idea is that the nuclei of the flames, which have dropped to the lower part which is rendered in symbolic form, are surrounded by sparks which glow in the shape of fire. One can believe that the ornaments rendered above the bud are blossoms or branches of trees which have caught fire. “As for the empty spaces in the carpet, they have been filled with depictions of men, horses, flowers and trees. The carpet’s interior has been surrounded on every side with a border peculiar to the Talysh carpet. At this point we have got say that the Talysh -- Lankaran carpets are woven in a narrow, oblong form and dyed with material colors extracted from plants. “As is seen in the second illustration, although the carpet’s background is given in white, the bud elements have been rendered in red which signifies flame, the edging surrounding the interior is dark and he ornamentation upon it is white. The general coloration used in the carpet is correct. The use of the bud element in Talysh-Lankaran carpets was considered doubtful until this day. But one can say based on materials acquired through research that the bud element was also woven into Talysh-Lankoran carpets. The carpet in the “Talysh-Buta” composition displayed at the exhibit proves this idea once again. “The emergence of the new type of bud composition called “Talysh-Buta” was a step onward in Azerbaijan’s carpet art. “One of the displays at the exhibit was the “Khan-tirme” [?] which was woven in the 19th century in Barda. [It is interesting that Barda still survives as a place name in the 19th c.] “The interior of this carpet is composed of buds organized by rows. These buds are arranged in four columns in both horizontal and vertical lines. With regard to the form of the bud elements in the carpet, it differs from the buds given in the “Talysh-Buta” composition carpet. The view of the buds rendered in the first row in this carpet is different from those in the second. Thus, the buds have been arranged in a column along the length of the carpet. They are contained in a zig-zag line rendered by the artist with great mastery. These zig-zag lines pass in back of every bud asymmetrically and increase the esthetic quality of the carpet. The zig-zag formed branch which contains every bud is reminiscent of the paired forms that were stylized above. The interior design in the carpet’s border is the “Hemenkemenchi” characteristic of the carpets of Karabagh. “Natural colors are used in the carpet. The zig-zag lines on the dark background are given in white. The carpet’s appearance recalls the tirmes [?] from India. “One of the carpets displayed at the exhibit is the “Balyg” pattern carpet.

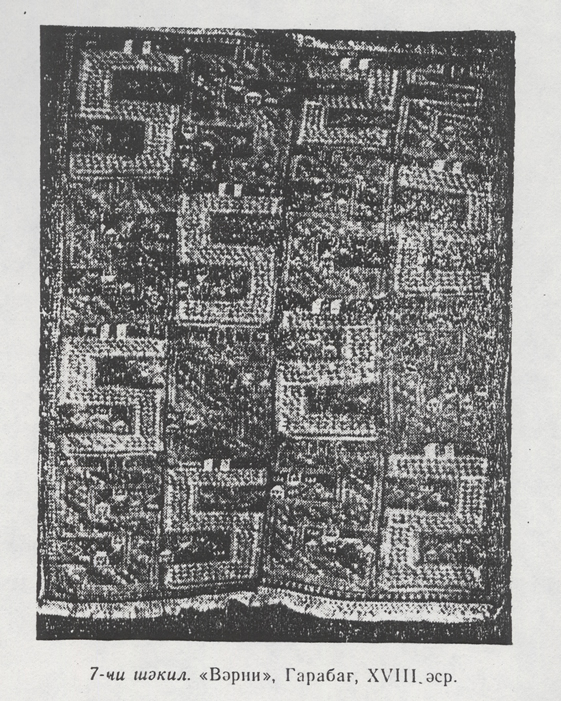

“At this point we must say that until the second half of he 19th century Karabagh was famous for its own carpets of various patterns. The city of Shusha was a major center for the commissioning of carpets and the carpet business in general. But dating from the second half of the 19th century the carpets produced in Shusha began to decline more rapidly than in other carpet-making regions due to the influence of foreign capital. It is known that the art of carpet-making which kept pace with the demands of the time or, more correctly, which could reflect in itself the manifestations of the social-political structure (like other forms of applied art) began to lose its esthetic characteristics and qualities at the beginning of the 20th century. Local craftsmen did not use the famous classical patterns due to the use of chemical artificial colors on one hand, and due to the demands of the marketplace on the other. In order to meet market demand at the end of he 19th and beginning of the 20th century new carpet patterns from Russia and Iran were introduced into Azerbijan’s carpetmaking in place of the old ornamental carpets. Among these one can point to the “Bagchada guller” (roses in the garden), “Sakhsyda guller” (roses in faience), “Bulud” (cloud) and other new carpet compositions. “Some carpet artists simplified and abbreviated the famous classical national carpet patterns in order to increase their income and reduce their expenditure of labor. One can see this in the “Balyg” type of carpet composition which was displayed at the exhibit. The carpet’s background is filed with plant ornament. Its interior, however, has distanced itself from the basic “Balyg” pattern of carpet composition and has been simplified due to the demands of time. The carpet’s interior is surrounded by a border called “sichan dishi” (mice teeth). The carpet’s background has been somewhat simplified: even its characteristic border is completely alien to our national ornamental art and has used the “flower stem” of the newer composition carpets which were created in the late 19th and early 20th century. The mice teeth in the carpet’s border, the trim and the border itself are border fields copied from European style. Primarily chemical colors have been used in the carpet. The carpet’s background is rendered in red, and the ornaments on it are in white and various other colors. “Among the examples of artistic carpets at the exhibit the palaz products on display from Baku, Karabagh and other regions also attract special attention. “The (“Sade killim”) was woven in Gobu village of Baku as a palaz-kilim weave. But Karabagh kilims differ from kilims woven in various other parts of Azerbaijan by their composition. These kilims are strongly patterned in gems of color and resemble Tabriz kilims in their weave. “Among the carpet products without pile displayed at the exhibit one of the objects which attracts attention is the Karabagh “Verni”.

“This verni was woven in the 18th century and consists of two parts. A number of fragments are located in the horizontal and vertical directions. The observation has been made that these fragments are in the shape of an animal, but it is also possible that these fragments are in the shape of a bird. Aside from this, a jejim from Karabagh was displayed at the exhibit. The jejim consists of 16 different parts. The ornamentation above make it possible to say that this jejim was woven in the village of Lemberan which was famous for its jejim products in the Caucasus. The wool yarns arranged in various colored rows that were used in weaving jejims are displayed on an oblong frame between the 16 jejim parts. In addition to this among the goods on display at the exhibit from Ganja for the Yelizavetpol Guberniya the “Khurjin” and the “Mafresh” which was sent from Karabagh also attract attention. The inner border of this mefresh is woven from Karabagh carpets; as for the small border, it has been woven using the interior borders from Baku carpets. “Carpets woven from silk at the exhibit also attract attention. As is known, carpets and carpet products from silk were also woven in Azerbaijan in the 19th century. A list of the carpets and jejims woven from silk which were displayed at the exhibit is given on the list below: “Gayana Atabeyova from Sheki city presented a silk carpet depicting the “Badamy buta” (almond bud”). Both the base (arish) [warp] and the woof (arghach) of this carpet are woven in silk. The carpet’s colors have been chosen tastefully and the work done with great effort. Because of its beauty and grace the carpet was considered one of the most beautiful exhibits at the exposition.

“In addition to those, the wool of local sheep which is considered the basic raw material in carpet production was received from a number of provinces and put on display at the exhibit. These are given in the list below:

“One can see from the list below the plants from which the natural dye was attained to dye the woolen yarns in the 19th century carpets from Azerbaijan.

“The works of high quality at the exhibit were evaluated by a special commission.

“Among the participants awarded a bronze medal:

“Among the participants awarded with certificates: [from]

“We can mention again that at this exhibit, along with the number of industrial and agricultural products on display, various kinds of sheep wool, agricultural plants, carpets and carpet products from Azerbaijan were singled out for their quality. “One of the important aspects of the exhibit was that by exposing a number of carpet-producing regions, carpets of new composition and carpet products hitherto unknown to us, we are able to cast aside the idea that the bud (buta) element was not used in carpets woven in the territories of Lankaran and Sheki; it proves once again that bud elements were used in carpets in these territories. “The carpets and carpet products displayed at the exhibit, by keeping in step with the social and economic conditions of the time, met the demands of the time with complete success. “The 1889 exhibit in Tblisi which drew thousands of visitors was an experimental school for future exhibits.“ [1] Alieva, Anakhanym, Carpets from Azerbaijan at the Caucasus Exhibit of 1889, Izvestia, Azerbaijan SSR, Literature, Language and Fine Arts Series, Vol. 3, 1968, pp. 92—104. [2] Kavkazskiy kalendar’ na 1890 g., Tiflis, 1889, p. 8; Katalog plan kavkaskoy vystavki predmetov sel’skogo khozyaystva, 1889 goda, pp. 18-19, p. 21 ff.; Shavrov, N.N., Opisaniye Kavkazskoy vystavki predmetov sel’skogo khozyaystva i promyshlennosti v gorode Tiflise v 1889 g. vyp. II, p.69—72, pp.117-118. (Shavrov was a respected textile expert.) [3] An alternate possibility, however, is either faulty understanding or sloppy writing by the author.

Copyright � Richard E. Wright, All Rights Reserved |