|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"What was the ensi before it became a hanging? -- Charles Grant Ellis, 1993 Turkmen carpets and carpet-like items have clear functions-- khali (carpet), torba (bag), iolan (band), and so forth. One, however, may not be so straight-forward, the engsi. For any such question the proper starting point is a relevant dictionary (c. 1950), all of which define the word as a small rug without gols used as a yurt door closing.1 The Turkmen language has a nasal "n" which shows up here; its transliteration into English therefore is engsi. Ensi is a Russian (no nasal "n") conceit; the pre-revolutionary literature occasionally did try to get it right, Dudin with enki, Felkersham, with enksi.2 It is useful to get at meaning via etymology, but in this case, perhaps not possible. Radlov's great Turkish dictionary3 does not include the term. In any event figuring out what if anything the word reveals is a matter for specialists; a clue might be that it may come from Persian.4 A Turkmen participant at the 1996 Askabad conference presented an illustrated overview titled "Origins of Turkmen Motifs". One particular in this wide-ranging talk about carpet types, designs, influences, and the like was a thought provoking comment that engsi is an ancient term for either an Iranian ruler or a place for a temple. This is apparently a fresh idea and worth a follow-up by someone with requisite skills. Engsis

have somewhat different sizes, bear an essentially uniform design,

vary in secondary and minor motifs, and reflect the properties (weave,

yarn, color) alleged (the underpinning links are quite shaky) to

characterize the anything but monolithic principal Turkmen confederations.

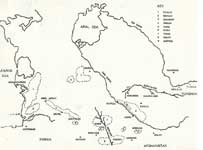

That these groups employed a common pattern fits well with their

17th century co-location on the Mangishlak peninsula prior to having

been pushed out by Kalmuks5 and scattered along the Amu

Daria river to the northeast as well as along the base of the Elbruz

mountains (Asgabad and beyond) to the southeast. (Figure 1) The

pattern’s persistence among these subsequently widely scattered

and to some extent isolated clans suggests that the design may be

fundamental. There is some thought that it is old;6 recent

carbon dating studies underscore this possibility.7 Please click on the small images to enlarge. 20th century

Soviet authors for the most part call the engsi a door

closing,8 and received wisdom in the West takes the matter

further -- “the common furniture of the tent entrance"9

-- hardly the case. It was felts which were ubiquitous closings.10

(Figure 2) On this, Baron Felkersham has a couple of interesting

observations: poor Turkmens used small felts which were “attractive,”

sometimes “adorned with embroidery and designs”; and,

other nomadic groups not engaged in carpet-making employed for the

south entrance of yurts ordinary felt “decorated with embroidered

designs of grapes, trees, birds and small animals”.11

Beyond felt, other materials regularly served the purpose: Bukhariot

fabrics12 and palas (kilims).13 (All

these, without gols, happen to meet the dictionary definition.)

Some Yomud yurts had wooden doors,14 (Figure 3) (Figure

4) (Figure 5) (Figure 6) as was also the case in Tekke Merv.15

A few engsis have corner loops and so do some main carpets;

each could be hung, the loops saying nothing about where; one period

photo shows a floor carpet hanging on a wall,16 something

also mentioned in travel accounts.17 In brief, the late 20th century view of door closings is too narrow. The European

and American encounter with the engsi took place more than

a hundred years ago. In 1885 A. A. Astaf'’ev published a book

of interior design18 as a result of his trip through

newly conquered Russian territory to the Akhal oasis. (Figure 7)

This review of Akhal carpets and embroideries, including engsis,

together with suggestions for their use in European interiors awakened

Russia to Turkmen textiles. Assertion that the book reflected an

existing practice19 is wrong. Rather, Astaf’ev

created a fashion, as is easy to see in the timetable of Russian

expansion into the area (early 1880’s), and made clear by

an 1888 visitor to Akhal who remarked on an abundance of rugs, noted

their absence in Russia, and predicted arrival once the railroad

(a military enterprise) was open to civilian traffic. The engsi

along with other Turkmen carpet materials indeed become popular

in Russia, and subsequently in Europe. (In part due to Russia’s

Central Asian exhibit at the Paris Exposition of 1900). (Figure

8) The engsi’s modest abundance today stems from

commerce beginning in this period; significantly, they were still

an export item in 1930.20 The common

door curtain canard gained a bit of mileage by the unearthing of

an 1885 newspaper sketch showing an apparent engsi covering

a yurt entrance in Pendeh oasis.21 Not brought to notice,

however, was a second illustration in the same hamlet showing a

doorway covered by a fabric, not an engsi. (Figure 9) (Figure

10) Also overlooked was the occasion which brought the correspondent,

a visitation by the Afghan Boundary Commission, along with the fact

that the newspaper text was written not by the correspondent but

by editors in London. Here, one needs to remember that Western and

Central Asia building exteriors frequently were decorated with textiles

on special occasions. Because of this, door curtains in evidence

on any given day can not confidently be taken for ordinary use.

An 1885 report of this visit also notes a "hanging carpet"22

which could have been either engsi or fabric. The sketch is one of the scant Turkmen evidences (there are a few Kazak and Khirgiz) of an engsi in a doorway. Richard Isaacson of the International Haji Babas has garnered some of these photos. Upshot, to tout one as “rare” certainly makes a point, but it isn’t the photo which is rare;23 it is the doorway engsi. An explanation

of such dearth, of course, would be interior use. And, interior

photographs of both Kazak and Khirgiz dwellings show decorated hangings

(reed mats, textiles) on the inside of doorways. (Figure 11) Photographs

of Turkmen interiors, however, seemingly seldom come to light. Felkersham,

author of the major and enduring work on Central Asian weaving,

noted that engsis "almost exclusively are met with

among the Pendins,"24 that is, at Pendeh oasis.

(Figure 12) This is his significant observation, not his comment about the objects being pretty and pricey. Late 19th c. Saryks, in the far southeastern corner of Turkmen territory, were the clans at greatest remove from their kin, the Russians, and European markets. Whether the makers of these engsis were Saryks, as some of the older rug books thought, or Salors is not of interest; both were in the area, the diminished Salor for the most part across the Persian border, but of the local culture. What to make of this remoteness isn’t clear; one reasonable thought is that perhaps Saryks and Salors clung longest to the old ways and that the engsi after all was intended for door use. Getting at original purpose is a difficult business; in this regard there are hints that this may have been as a prayer rug. On this score, however, the setting is inhospitable. Turkmens were nominal Mohammedans and not observers of ritual; turn of the century travellers and writers about carpets noted that Turkmens did not perform ablutions, nor build mosques, nor use prayer rugs.25 Not a promising milieu for the engsi as prayer space. While it is

not clear what if anything might have served as such in Transcaspia

(the bulk of Turkmen territory, a province of Imperial Russia, erstwhile

part of the Soviet Union, today the Republic of Turkmenistan) there

is an obvious Central Asian prayer rug, one made in the Bukhara

khanate by sedentary peoples (Turkmens and Uzbegs) along the middle

reaches of the Amu Daria river. (Figure 13) The image on

the rug -- a mihrab -- was known to Uzbegs as a pishtak

(gate), and the two TV antenna-like lines (regularly atop mihrabs)

were seen as a "stork's nest".26 The same embellishment

occasionally appears in Anatolia. Substantial weaving in the Bukhara

khanate began only in the 1870's,27 and shows obvious

Persian inspiration. While the Bukhara prayer rug comes in part

from Turkmen weavers, it stems from an external tradition. The older Russian

literature is murky in its view of the engsi. (Figure 14)

Early 20th century authors noted that engsis and prayer

carpets were similar in appearance and easily confused.28

Felkersham, for example, illustrated a "Pende engsi"

(so-called, but not by him, Saryk type with six small pentagonal

motifs across the top), a "Yomud namazlyk" with

a pronounced mihrab-like inner field, and also a "Yomud

engsi" with neither niche-like field nor a topmost

row of small mihrab-shaped motifs.29 (Figure

15) (Figure 16) (Figure 17) The only rug

book written by Turkmens (unfortunately neglected; it is, after

all, their art) has 13 illustrated engsis; those which

are labeled Yomud and Ersari are without small mihrab-like

motifs; Saryk and Tekke items have them, with one exception in each

case. The antenna atop the Beshir niche nowhere appears.30

(The book may be making the same the point as did Felkersham.) Icons are not only a matter of mihrabs. Travel books, Russian survey data,34 and the old Russian carpet literature all mention that Turkmens said the engsi pattern was a representation of the architectural plan of the Kaaba -- "it designates the Kaaba" -- Islam's sacred site. A Turkmen’s paper at the 1996 symposium in Asgabad listed seven sources for designs on engsis, four of them religious, one of these, the Kaaba.35 The Kaaba’s

housing was covered by a cloth which was sacred. (Figure 18) A centuries

old Ottoman tradition entailed annual sending to Mecca of a new

fabric; fragments of the one it replaced were retrieved and venerated.36

In 1050 the covering was described as white "... striped with

two bands of large cloth...in the four faces of fabric... (was)

the mihrab image, repeated."37 If one wishes

to, bands and mihrabs may be seen on the engsi’,

but so can other things. The need to tell the infidels something

hardly means that a claim that the Kaaba is the source makes it

so. Early travellers to Persia, for example, were told that a mihrab

was a representation of the dome of a mosque. But a garden also

is an appropriate (heavenly) image for a prayer space, and gardens

in western Asia with walkways and water courses can be seen on the

engsi. (Figure 19) Scribes in the West have occasionally

indulged in thoughts that what is represented thereon is the cosmos,

also a favorite pastime of Turkmen researchers. A bit of a stretch

but within the bounds of speculation, but to base such thoughts,

as some do, on the secondary and tertiary motifs is to enter a quagmire. Some Turkmens

may have used prayer carpets, Dudin having mentioned the Salor and

the Yomud.38 Yet Transcaspia (Figure 20) kustar'

summaries from 1882 -- 1914 (serial reports on government-supported

home craft industries) use the term namazlik only in the

district (Krasnovdosk) which had an essentially Yomud (along with

some Chodor) Turkmen population.39 This difference could

have arisen merely from inconsistent nomenclature among the five

administrative districts, but nevertheless may point to something

other than engsis having been made in Yomud territory as

prayer carpets, something hinted at by an 1892 comment on the work

of Yomud women in a particular district, Karakalin, which noted

prayer carpets “in beautiful and various” designs using

cotton for white.40 For Krasnovdosk in 1900 reports state

that prayer carpets constituted 38% of pile rug production, and

in 1911, 61%. The rug counts in such documents are modest, only

hundreds per year. Another compilation, in a special fact-finding

survey, recorded all Transcaspia rug production in 190841

and reported a prayer carpet share of 30% (738 rugs). Felkersham

calls a small hexagonal rug with a field dominated by a niche shape

an Orgurjali prayer carpet.42 (Figure 21) (Orgurjalis

were Yomuds.) Within the niche image is a small five-sided motif;

if this is thought of as of a representation of a Karbala briquette

the rug would be Shiiah, which is possible, for Turkmens in the

vicinity of Asterabad were Shiiah.43 Also present on

the image are the two small antennae. (Figure 22) It needs quickly

to be said that other members of this genre do not have the possible

brickette image. Soviet authors call very similar items saddle cloths.44 One unaccountably cites the Felkersham illustration as an "Ersari horse trapping?"45 An explanation, per Occam’s razor, ie, use the simplest, is that the field was determined by the rug’s hexagonal shape, this in turn dictated by horse anatomy. But this answer does not attend to the possibility of a Karbala brickette image, there by weaver choice, not the horse’s. To think of the engsi as a once religious artifact is to encounter problems. Why would it be that marginally Muslem Turkmens, viewed by their rulers and Uzbeg town dwellers as country bumpkins, employed a design derived from the Kaaba? But there may be an interesting albeit speculative answer. Timurid (1400 – 1500) court art used architectural forms in the decoration of fabrics;46 some designs, for example, long ago surfaced as a promising source for the Turkmen gol.47 The Uzbeg rulers who succeeded the Timurids admired and aped their culture.48 A Turkmen link to this art to some extent necessarily would have had an economic base. Altogether to be expected -- for hundreds of years Central Asia’s nomads and semi-nomads traded with the oasis cities, offering wool (raw and in finished form) in exchange for goods (salt, sugar, metal) not obtainable on the steppes. In the modern period (17th c. onward) Turkmen commerce in rugs and related items would have been with Uzbegs, as is apparent in 17th century Urgenj and Khiva,49 within the then Turkmen heartland. The Turkmen to Uzbeg connection was remarked on by one Central Asia specialist who observed that Turkmen weavers made carpets for "an Ozbeg taste".50 Perspective The foregoing sketch does not show what the engsi was or is, but rather contains bits and pieces of possibilities: the apparent absence of niches in the putative Yomud oeuvre, presence or absence of antennae atop mihrabs, the mention of prayer rugs in Yomud country conceivably not in engsi format, and so forth. All of which seems to point to the value of further inquiry. For, indeed, the rug bazaar's “common furniture” cliché trivializes what may be a significant material cultural artifact. The data underline a self-evident proposition: the past can never be characterized by simple projection back from the present. In brief, the

mix of observations is rich: -- mihrabs, Karbala brickettes,

Kaaba coverings, horse furniture, namazliks -- with their

traces clouded by the passage of time and Soviet repression of national

consciousness of the peoples of Central Asia. Much needs a better

look; there are substantial matters – religiosity, commerce,

the cluster of engsi references to the Pendeh area, and

the fact that an allusion to the Kaaba is abundant in period literature.

A good deal to think about.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||